THE ADVENTURES OF A CAT AND A FINE CAT TOO!

Love and war

Hum Villa, the house which had been left me by my deceased cousin, stood a little back from the main street, and although surrounded with smaller dwellings, was yet quiet and retired.

This was owing to its garden, and to several fine trees which shaded it; one of them particularly, an ancient oak, that stood by the right-hand corner of the grounds, cast its broad and knotted arms over a rustic bench, and made a delightful retreat from the warmth of the summer sun.

It had been the favourite spot of my departed relation: here she would come, in the long afternoons, and, reclining on the chair, with a book in her hand, read a page or two, then stop to listen to the birds which twittered in the topmost branches of the tree, or watch the busy insects at her feet, as they ran about intent upon their pursuits of business or enjoyment.

There could not have been a stronger proof of the goodness of her disposition, than to note the friendship which existed between her and the timid birds that frequented the garden. Perhaps it was the love of music in both that created a kind of sympathy between them, for I have often hidden myself within a short distance of her seat, in order to watch the proceedings of herself and feathered friends.

When they observed her alone, they would hop down from branch to branch, until they were almost within her reach, when, after hesitating a few moments to see that no other Puss was near, they would leap down upon her seat, upon the ground, upon her very shoulder, and begin their songs. Then followed such a twittering and chattering, while their wings trembled with excitement, until, at some noise perhaps which I myself had made, they would start from their places, and in an instant fly up, up, until they had put the whole height of the tree between them and the supposed danger. Often had I wished to obtain from them a similar confidence; often by various inducements of food and voice endeavoured to lure them down. My persuasions were all useless: they would put their little heads on one side, and talk a little among themselves, apparently debating whether it would be advisable to accept my invitation; but some old and cautious birds, I suppose, advised them to refuse my advances, for they never dared to partake of the meal I had spread for them until I had myself taken my departure.

Once only, after my cousin's death, when I was seated in the place, and in the attitude she herself was accustomed to assume, did a venturesome little creature undertake to pay me a closer visit. But I was not flattered by the attention, for it evidently mistook me for her who was no more; as, scarcely had it perched upon the arm of the bench, at the opposite end to where I was sitting, and glanced at my face, than it flew off in the greatest alarm to communicate its terrors to its companions.

Although I thus failed to secure the confidence and friendship of my cousin's allies, there were other sources of amusement which this quiet nook afforded me. Unseen myself, I had a view of at least a dozen dwellings, and of the antics played by their inhabitants. It is astonishing to a Cat of perfect good-breeding to observe the propensity of the uneducated classes to climbing and creeping about in the most elevated and dangerous positions. Within a few doors of my own house resided an old Tom, whose business I never could guess, but who was at home all day sleeping or smoking, and went out to his occupation at nightfall. Instead however of taking his rest within-doors, as one would have thought it most comfortable to do, he always had his doze in the open air, and no place would suit him but the very edge of the roof of his house, with his legs and tail generally swinging in the air. It was a wonder to me that he did not either fall or get pitched off; for his sons and daughters, an immense tribe of unruly Cats of all ages, were constantly on the roof too, chasing each other about, rolling over one another's backs, and often hissing and spitting at each other in a most shocking and boisterous way. Their poor mother had lost all control over them, and after trying, as I had often seen her, to get them into more orderly habits, she was forced to give up the struggle and allow them to take their own course.

These rude creatures had taken a particular dislike to me: first, because I had reproved the young Pussies for their behaviour, as being very unbecoming their age and sex; and secondly, on account of my having forbidden them entering my grounds to chase the poor birds who lodged in the trees.

As to the latter particular, they at first set my wishes at defiance, paid no attention to my remonstrances, and actually one day came over the palings into my garden and carried off a poor little bird which had fallen from its nest. I was then obliged to have recourse to other measures. I hired an old Tom to scare them away, which he did so effectually that they never ventured to come within his reach. But their hatred to me became all the greater; and as from their lofty position on the housetop they could see right into my garden, whenever I ventured to walk there, they saluted me with all sorts of names, called me a "Prude," the "Schoolmistress," and anything else which they thought would annoy me, so that I was pleased to have the shelter of my arbour, where I could be out of sight and yet enjoy the fresh air.

It is always unpleasant to be at variance with one's neighbours, and no doubt animals ought to make many sacrifices to prevent it, and live in harmony together; but it would have been weakness to give up the happiness and even the lives of my favourite birds—the favourites too of my poor dead Cousin—in order to please the unruly offspring of my singular neighbour. A state of war might therefore be said to exist between us, and I was not long in feeling the effect of the malice I had unwillingly provoked.

And here I must speak of an adventure which, although quite innocent in itself, caused me a great deal of pain, and forced me to become, for a long time, a wanderer from my native city.

One evening, when seated in my arbour, after my pupils were dismissed, a servant came to inform me that a strange Tom was in the parlour, who desired to speak to me. I at once went in, and observed a tall, foreign-looking figure, who introduced himself as Senhor Dickie. He explained that he was an artist; had met my cousin in his own country; had been invited by her to pay her a visit at her house in Caneville, if ever he should come that way; that he had arrived that morning, and learnt to his surprise that she was no more; that he had nevertheless taken the liberty to come to the house, in order to see the surviving relative of one for whom he entertained a warm friendship, and express his sorrow for her death.

He said all this in so Cat-like a tone, and his beautiful green eyes had so tender an expression when he spoke of my poor cousin and looked at me, that I quite felt for him, and we had a long chat together about the goodness of her who was no more. We had talked ourselves into so good an understanding, that, when he went away, I asked him, as a matter of course, to come and see me again; nor could I indeed avoid inviting him to that house to which, had my cousin been alive, he would have been, no doubt, very welcome.

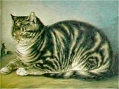

Senhor Dickie came often to see me, and every time he came the better did we become acquainted. We chatted together about all sorts of things; we sang duets together (he had a fine bass voice); and at last he requested permission to take my portrait, which he did, as represented in the Frontispiece to this Autobiography.

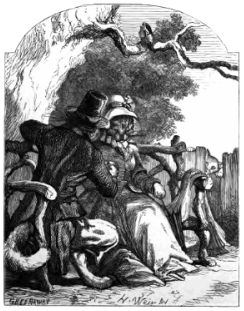

It was on occasion of one of these visits that, on a hot summer's afternoon, we sat in the arbour together. I do not know how it was we had walked out there, whether at his wish or at my invitation, but there we sat, and I remember thinking—for I said nothing—that nature had never appeared more beautiful. The flowers seemed to be tinged with more lovely colours; the green of the trees wore a richer and deeper hue; the butterflies looked as if they had put on their most dazzling suits in celebration of some holiday; and the birds appeared to be holding high festival beneath the glowing heavens, and fluttered and twittered and sang with greater glee than they had ever seemed to do before. My companion's voice, low and deep at all times, was surely softer on that evening than I had ever known it; and his eyes wore a look of tenderness which made me cast mine to the ground, for fear he should discover the same expression in my own.

He had just placed his paw on mine, and opened his mouth with the intention of making a speech, which I am sure would have been a sweet one, when I saw his face change, his back set up, his tail swell out and move angrily to and fro, while his ears fell back, and an angry hiss whistled fiercely from his close-set teeth, as he looked towards the palings. I turned quickly round in the direction of his eyes, and, to my horror, saw one of the malicious creatures of the house close by, who was watching us with intense satisfaction through a break in the fence, and grinning at the tender scene which I have been attempting to describe.

When she saw she was discovered, she started off towards her own house, uttering, as she went, a hoarse Mul-rou-u-u! but before she had got halfway there, my companion had leapt over the fence and pounced upon her, to punish her for her indiscreet curiosity and impertinence. The screams of the young Puss, and the loud and angry tones of Senhor Dickie (for I grieve to say he swore dreadfully), brought all her family out-of-doors, who, seeing the chastisement, and without inquiring whether it was deserved, fell upon poor Senhor Dickie in a body, and so ill-treated him, tearing his very coat off his back, that he was forced to run limping away, nor did he ever again venture to make his appearance in the neighbourhood.

When my poor companion had thus been forced to take to flight, all the anger of the enraged creatures fell on me. As I made my way into the house, hisses, screams, the most horrible sounds the Cat tribe are capable of uttering, broke from the numerous family; and, what was worse, the uproar having brought all my neighbours out-of-doors, the greatest falsehoods were told them about the origin of the dispute, and I had not strength to raise my voice in order to explain the truth. Finding there was no chance of obtaining justice, or even a hearing, from my prejudiced judges, I walked slowly into the house, apparently indifferent to what they were saying about my slyness and my cruelty; but as soon as I got in-doors all my calmness vanished. Sorrow, confusion, anger, so warred together in my bosom, that my Cat's frame could bear it no longer. I fell to the ground in a fainting fit, and was conveyed to bed by my servants, where I remained several days, a prey to as much unpleasant feeling as if I were really the cruel Puss my neighbours accused me of being, and as if it were really true that I had persuaded poor Senhor Dickie to fall upon the little spy out of spite towards her family.