THE ADVENTURES OF A CAT AND A FINE CAT TOO!

Introduction

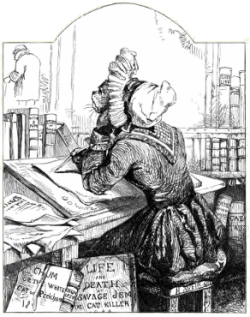

I was about to address my readers with the usual phrase, that "at the request of friends" I had collected the scattered memorials of the chief events of my life, and now presented them to the reading world, in the hope that some lesson might be learnt from them, which could be useful to the inexperienced when similarly situated. But I will be more candid, and say rather, that "to please myself" I have put into a complete form the recollections in question; not however without the wish that they may prove of service to Cat, ay, and to Dog, and other kind. There never was a life spent in this world but that its history could teach a lesson; for, though every life has peculiarities of its own, and may be varied in a thousand ways, the wishes, the resolutions of most of us do not take a wide range, nor does it require a very extensive circle to limit them all.

I would not however have my readers imagine that vanity alone has induced me to record my experiences. No; I have had another, and I think a higher motive. I wished to convey to the intelligence of all animals capable of understanding the language of Caneville, some portions of the history of a real Cat; and, by so doing, try to remove from the minds of many the opinion that she is a creature ignorant of the finer feelings, oblivious of gratitude, incapable of strong attachments, and so uncertain in her temper as to scratch and bite even, one minute, the paw she has been licking and fondling the moment before. I wished to prove that the same natural disposition holds good with our race as with every other; that some of us are, from our birth, kind, rough, loveable, cruel, tender-hearted, and ferocious, just as other beasts that wear a tail or come into the world without one; and that this temperament may be modified, and even changed, by education and treatment, precisely as the dispositions of other animals.

It is a cruel wrong done to our race to exclaim, as many do, that "Cats have no attachments, no tenderness; that there is always a lurking fierceness in their hearts, which makes them forget, with the first mark of roughness or ill treatment, a thousand benefits which they may have formerly received." I deny it wholly. I, a Cat, affirm that, with few exceptions, there are no animals more loving or more tender. Look at the care which a respectable married Puss bestows upon her numerous offspring! Can any mamma more carefully wash or tend her darlings? Will any show greater willingness to forego her own occupations, in order to fondle and descend to be the playmate of her little ones? Does any display a firmer courage to defend them? And if she should give way to a little expression of feeling when her tail is trodden upon or pulled, or be betrayed into an angry growl when her territory is invaded, what then? You would not have her show so little spirit as to receive every insult unnoticed, or return a quiet "thank you" for the pain, physical or moral, which has been inflicted on her. How would you, dear reader, act if your tail were wantonly pulled, or if yourhouse were to be entered by an ugly stranger without invitation?

We most of us laugh at our good friends the Sheep, and indulge in many a sly joke at their stupidity. "What can be more absurd," we say, "than that habit of theirs of constantly playing at 'follow my leader,' and putting themselves into all sorts of disagreeable situations in consequence?" But are we any better ourselves? Are not wealways following some leader?—always imitating somebody, and running in crowds hither and thither because so-and-so are running there too? And thus it is thatopinions, once uttered by some great animal in authority, are taken up and repeated by his imitators, and are looked on as the very essence of wisdom, while they are often, in fact, no other, when examined, than untrue or mischievously unjust. Such are the pet sentences I have alluded to, wherein Cats are described: a whole race is sometimes condemned because a few members of it have proved unworthy; and a tribe gets a bad name because some animal of influence, a Jackass perhaps, brays out that "they are all worthless."

It has been often observed, and I therefore do not profess to utter an original idea by remarking it again, that when our prejudices are enlisted in favour of or against any object, every circumstance is turned to its advantage or the reverse. If we have done an animal a kindness, we are ready to do him another; if we have inflicted on him any injury, we are not at all indisposed to add a fresh one to it. And so it has happened that our numerous family, having been by many ill treated, are constantly exposed to kicks and insult from those same parties, for no other reason than that they have kicked and insulted us before. The meekness of our disposition has been distorted into hypocrisy; our quiet has been called "meditative treachery;" and our natural and innocent instincts have been styled "the proofs of a sanguinary temperament." Our every look has been perverted by our enemies into a moral squint; and our simplest caress and naturally fondling way have been set down as the strongest marks of a Jesuitical heart. In fact, in the eyes of many, nothing we can do, no step we can take, but is considered evidence of our wicked disposition; and we are not unfrequently loaded with abuse for the very things for which beasts that have a better name get love and commendation.

How happy it would make me if I thought the perusal of these few pages would induce any one to pause and reflect before condemning any one animal! And here I do not refer to my own race alone, but to the world of beasts at large; whether the Lion, creating a sensation in the class to which he belongs, or the Ass, laughed at for his stupidity in the circle to which his position in life assigns him. The same animal would often be judged differently if differently situated: were the Lion and the Ass, by some freak of nature, to change places, the stupidity of the latter would be set down as wit, and his every saying would be applauded; whilst the Lion, instead of being looked on as the perfection of nobleness and beauty, would be styled a surly brute, and considered at the best no better than a bore.

I think I hear some of my readers exclaim, "Who is this old Cat, forsooth, that she should thus presume to teach us lessons? The 'itch for scratching' must be very strong upon her that she should insist on swelling her tale in so outrageous a manner!" I own my fault, and will bring my musings to a stop.

My wish was to meet my readers with a friendly rub; my desire was to part from them with a gentle warning. Above all, my wish was to have them think of me kindly; for, though a Cat, and no longer young,—though no more possessed of those graces which once distinguished me, when the eye, as I have been told, felt pleasure in gazing on my form,—my heart still beats warmly, tenderly, and without envy, and would feel no common joy if it thought it had not dwelt in this earthly abode in vain.