THE ADVENTURES OF A CAT AND A FINE CAT TOO!

Kittenhood

There is nothing like beginning at the very commencement of a story, if we wish it to be thoroughly understood; at least, I think so; and, as I wish my story to be clear and intelligible, in order that it may furnish a hint or a warning to others, I shall at least act up to my opinion, and begin at the beginning,—I may say, at the very tip of my tale.

Being now a Cat of some years' standing (I do not much like remembering how many), I was of course a Kitten on making my entry into life,—my first appearance being in company with a brother and three sisters.

We were all declared to be "the prettiest little darlings that ever were seen;" but as the old Puss who made the remark had said precisely the same thing at sight of every fresh Kitten she beheld, and she was accustomed to see ten or twelve new ones every week, the observation is no proof of our being very charming or very beautiful.

I cannot remember what passed during the first few days of my existence, for my eyes were close-shut till the ninth morning. I have an indistinct recollection however of overhearing a few words which passed between my mother and a friend of the family who had dropped in for a little chat, on the evening of the eighth day.

The latter had been remarking on my efforts to unclose my lids, to obtain a little peep at what was going on, when my good parent exclaimed,

"Ah! yes, she tries hard enough to stare at life now, because she knows nothing of it; but when she is as old as you or I, neighbour, she will wish more than once that she had always kept her eyes closed, or she is no true Cat."

I could not of course, at the time, have any notion what my mother meant, but I think, indeed I am sure, that I have discovered her meaning long ago; and all those who have lived to have sorrow,—and who has not?—will understand it too.

I had found my tongue and my legs, and so had my brother and sisters, before we got the use of our eyes. With the first we kept up a perfect concert of sounds; the legs we employed in dragging our bodies about our capacious cradle, crawling over each other, and getting in everybody's way, for we somehow managed, in the dark as we were, to climb to the edge of our bed and roll quickly over it, much to our astonishment and the amusement or annoyance of the family, just as they happened to be in the humour.

Our sight was at last granted us. On that eventful morning our mother stepped gently into our bed, which she had left an hour before; and, taking us one by one in her maternal embrace, she held us down with her legs and paws, and licked us with more affection and assiduity than she had ever bestowed on our toilet before. Her tongue, which she rendered as soft for the occasion as a Cat's tongue can be made, I felt pass and repass over my eyes until the lids burst asunder, and I could see!

And what a confusion of objects I first beheld! It seemed as if everything above was about to fall upon my head and crush me, and that everything around was like a wall to prevent my moving; and when, after a day or two, I began to understand better the distance that these objects were from me, I fell into the opposite error, and hurt my nose not a little through running it against a chair, which I fancied to be very much further off. These difficulties however soon wore away. Experience, bought at the price of some hard knocks, taught me better; and, a month after my first peep at the world, it seemed almost impossible I could ever have been so ignorant.

No doubt my brother and sisters procured their knowledge in a similar way: it is certain that it cost them something. One incident, which happened to my brother, I particularly remember; and it will serve to prove that he did not get his experience for nothing.

We were all playing about the room by ourselves, our mother being out visiting or marketing, I do not know which, and the nurse, who was charged to take care of us, preferring to chat to the handsome footman in the tortoise-shell coat over the way, to looking after us Kittens.

A large pan full of something sticky, but I do not remember what, was in a corner; and as the edge of it was very broad, we climbed on to it and peeped in.

Our brother, who was very venturesome, said he could jump over it to the opposite brim. We said it was not possible, for the pan was broad and rather slippery; and what a thing it would be if he fell into it! But the more we exclaimed about its difficulty, the more resolved he was to try.

Getting his legs together, he gave a spring; but, slipping just as he got to the other side, his claws could not catch hold of anything to support himself, and he went splash backwards into the sticky mess. His screams, and indeed ours, ought to have been enough to call nurse to our assistance; but she was making such a noise herself with the tortoise-shell footman, that my brother might have been drowned or suffocated before she would have come to his assistance. As it was, he managed to drag himself to the edge without any help at all; and as we feared that all of us would get punished if the adventure were known, my sisters and myself set to work and licked him all over; and then getting into bed, we cuddled up together to make him dry, and were soon fast asleep.

Although the accident was not known at the time, we all suffered for it; for my brother caught a dreadful cold, and myself and sisters were ill for several days, through the quantity of the stuff we had licked off my brother's coat, and one of us nearly died through it.

As we grew stronger and older, we were permitted, under the care of our nurse, to go into the country for a few hours to play. It may be perhaps thought, from what I have said, that nurse's care was not worth much, and that we might just as well have looked after ourselves, as the poorer Kittens of our city were accustomed to do. But this was not precisely the case; for when nurse had nobody to chat with she was very strict with us, I assure you, and on such occasions made up for her inattention at other times. That unlucky fondness of hers however for gossiping, was the cause of a great deal of mischief; and about this time it partly occasioned a sad misfortune in our family. I said partly, because the accident was also due to an act of disobedience; and as the adventure may serve as a double warning, I will briefly relate it.

It was a lovely morning in early summer; the sun shone gaily upon the city, looked at his brilliant face in the river, danced about among the leaves of the trees, and polished the coats of every Cat and Dog which came out to enjoy the beautiful day he was making.

To our great delight we were allowed to take a long walk in the country. Two of our cousins, and a young Pussy who was visiting at our house, were to accompany us; and nurse had strict charge to prevent our getting into mischief. Before we started our mother called us and said, that, although she had desired nurse to look after us, and take care that no harm should happen while we were out, she desired also that we should take care of ourselves, and behave like Kittens of station and good-breeding, not like the young Cats about the streets, poor things! who had no home except the first hole they could creep into, no food but what they could pick up or steal, and no father or mother that they knew of to teach them what was good. Such creatures were to be pitied and relieved, but not imitated; and she hoped we would, by our behaviour, show that we bore her advice in mind. "Above all," she added, "do not let me hear of your climbing and racing about in a rude and extravagant way, for a great deal of mischief is often done by such rough modes of amusement."

We hastily promised all and everything. If we had kept our words, we should have been perfect angels of Cats, for we declared in a chorus that we would do only what was good, and would carefully avoid everything that was evil; and with these fine promises in our mouths, we started off in pairs under the guidance of nurse.

We soon came to the wood, situated at some distance from the city; and, walking into it, shortly arrived at an open space, where some large trees stood round and threw broad patches of shade over the grass.

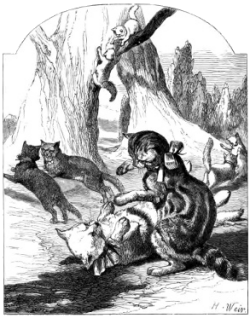

We at once commenced our gambols. We rolled over one another, we sprang over each other's backs, and hid behind the great beech trunks for the pleasure of springing out upon our companions when they stealthily came to look for us.

In the midst of our fun we observed that nurse had gone. We had been so busied with our own diversions that not one of us had observed her departure; but now that we found it out, we set off to discover where she had strolled to. We observed her, after a few minutes, cosily seated on a bank of violets, near the very same tortoise-shell footman, who lived opposite our house, although how he came there we could not imagine. Nor indeed did we much trouble ourselves to guess. Seeing she was so engaged we returned at once to our sport, and played none the less heartily because nurse was not there to curb us.

I remember, as if it were only yesterday, the scene which followed. I was amusing myself with one of my pretty cousins, who was dressed in white, and was about my own age. I had thrown her down on the grass, and was patting her with my paws, when I heard a scream; I turned quickly round, just in time to see one of my sisters falling from a tall tree, to which she had climbed with our young visitor, when, all of us running up, we discovered that, on reaching the ground, she had struck her head against a sharp stone, and was now bleeding and without motion.

Our cries brought nurse to the spot, who, as soon as she discovered all the mischief that had been done, without saying a word started off with all swiftness, with her tail in the air. We thought she had gone to fetch assistance or to inform our mother of what had occurred; but as she did not come back, and evening was fast setting in, we thought it best to proceed towards home, although we did not much like meeting our parents after what had happened.

There was no help for it however; so, giving a last frightened look at our poor little sister, who was now quite dead and cold, we walked sadly homewards, and reached the house just as night was falling.

I pass over what ensued,—my mother's grief, and her anger against nurse, who, by the bye, never came back to express her sorrow; I pass over also my mother's remarks upon the occasion; but I may observe, that they, added to the sad accident itself, made so deep an impression upon me, that whenever I felt inclined to disobey my good mother's admonitions, the image of my dead sister would rise up before me, and, although it did not, alas! always prevent my being wicked, it often did so, and on every occasion made me feel repentance for my error.