THE ADVENTURES OF A CAT AND A FINE CAT TOO!

Dangers

My Father was what is called a sporting character. The quantity of rats he caught, and of birds he ensnared, was almost incredible; and the fame of his exploits spread throughout the neighbourhood.

A taste of so decided a kind, and a dexterity so remarkable, not unnaturally extended to his offspring; and before we had attained our full growth, we had all killed our rats and caught our birds.

To indulge this passion my father had two little huts, which he called hunting-boxes, both conveniently situated for his favourite pursuits. One was on the bank of the river, near some old timber, a famous haunt of the rats, who had a colony close by; and the other was in a wooded spot, overhung with trees, among which the birds loved to linger, although many of their number waited there to their destruction.

My mother, who had been very delicately brought up, and who had very strict notions concerning propriety in female Cats, was very anxious to keep myself and sisters away from either of these places, although she had, of course, no objection that our brother should visit them; but, as we had been all educated together, we Pussies thought it rather hard that Tommy should go whilst we were forced to stop at home; and, as our father was very indulgent, we often managed to slip off unawares and join him and our brother, trusting to his kindness to save us from our mother's displeasure.

I happened to learn one day that several sporting Cats had been invited to a great hunt, the place of meeting being my father's box beside the river. I felt the greatest desire to be present at one of these affairs, as Tommy's account of them had made my very mouth water. I knew it would be vain to ask my mother's consent, as she would not only refuse it, but would take measures to prevent my getting out if I felt inclined to disobey. I therefore kept very quiet about the matter, but resolved within myself to indulge my inclination, and get a peep at what was going on.

"It will be easy," I thought, "to do so without any one being the wiser; and even if I should be found out when I am there, I am sure father will not be angry."

With this reflection, on the appointed morning I slipped off unperceived, and, arriving at the hut a good hour before the time fixed, I climbed up to the top by the help of a tree which grew near; and stretching myself on the roof, with my eyes peering over the edge, just where a branch of the elm I had got up by afforded me a shade, I waited for the company.

They were not long in coming. My father and brother arrived first, and a servant with some provisions; they were soon followed by an immense White Cat with one eye (but what a fierce one it was!) and a handsome Tabby, his son. Next came a Cat they called Mr. Dick, who wore a shabby grey coat, rather torn and patchy, and whose tail was ragged and dirty, yet to whom everybody showed a great deal of attention, because, as I afterwards learnt, he was very rich and ill-tempered. There were two or three others that I don't well remember, but which made the number complete.

As soon as they were all assembled, they sat down to breakfast; and I could see them through a chink in the roof as they demolished their meal. I had taken the precaution to bring something to eat too, and I now devoured it with much appetite; for the fresh morning air and my elevated position had made me hungry. As I munched my food, I could hear the conversation below, and was much edified by the terrible stories which some of them told about the fights they had had with rats as big as themselves, and the fierce battles they had won. I could not help observing that although Mr. Dick's adventures were much less wonderful than those of any other Cat present, they were heard with a great deal more interest, and were applauded as infinitely more remarkable.

Word was now given to prepare for the coming hunt, and every Cat rose from table, and came out among the timber. Hiding themselves behind various logs, my father stood up and uttered a loud cry, which I afterwards learnt was a signal for a quantity of ferrets, trained for that purpose, to rush into the rats' holes to drive them out. As the rats have the greatest horror of these creatures, they sprang from their hiding-places in the wildest confusion, and were at once pounced upon by the hidden Cats.

What a scene of confusion followed! The rats, who were scampering along, over and under the logs to escape from the hated ferrets, were suddenly aware of the presence of more detested and more formidable enemies, as, one by one, the sporting Cats jumped up, and made a dash at their bewildered prey.

My excitement at this spectacle was almost more than I could bear. As the growls of my friends and kindred, joined to the screams of the flying rats, became audible, and I could see the lashing of tails and the fierce glances of bright eyes, accompanied every now and then by a chase where some rat, which had been hiding beneath a log, suddenly leaped across the open ground, I sprang to my feet, I ran hither and thither, with my tail swollen to twice its natural size, from my eagerness to participate in the so-called sport of my relations.

I was not however destined to remain without my share of it, although I did not stir from the spot where I had been concealed. I said that a tree grew close to the hunting-box, on the roof of which I was placed, and that it was by its help that I had climbed to my present elevation. A large rat, with a body not very much smaller than my own, which had managed to escape from the fight where so many of his friends and relations had fallen, sought about for a place of refuge. Espying the tree, and seeing that all his enemies were at that moment too much engaged to attend to him, he sprang up the trunk and came rapidly towards me, little expecting to find another of his foes so far away from her companions. I watched him come, and resolved in my own mind that he should not escape, although my heart beat a good deal at the idea of the encounter.

The rat sprang on to the roof, and was going to scamper over it, when his fierce little eyes,—and quick nose too, no doubt, for it moved incessantly,—spied me out, crouching at a short distance and ready to spring. He stopped an instant, as if considering what it were best to do, then, thinking perhaps that if he attempted to run I should be at once upon his back, and, I suppose, observing from my look that I was only a Kitten after all, he came boldly towards me, and, just as I was about to pounce upon him, he sprang, like a flash of lightning, at my face, and made his sharp teeth meet in the most tender part of my nose. In vain I shrieked and beat the terrible creature with all my strength upon the roof; it was to no purpose that I fixed my sharp claws into his sides, and tried to tear him from his hold; he would not let go, and the pain was at last so great, that, squeezing him in my paws, I rolled over and over in my agony. The roof was sloping, and slippery besides with dew, so that, blinded with terror and not knowing what I did, I gradually got near the edge, and at last tumbled over on to the party below. I should probably have been much hurt by the fall, as I was not yet clever enough to tumble on my feet, but that I came down plump upon the back of a very stout Cat, who was standing a little aside quite tired out with his exertions. Him I knocked completely over, sending him flying, to his astonishment, a dozen paces off; the rat, detached from my nose by the shock, was at once strangled by my brother; and the rest of the party, running up to me, whom they thought dead, were not a little surprised to find the daughter of their friend. My father himself took the matter very quietly; I heard him exclaim, "I say, Tommy, how came your sister here? There will be a fine noise at home when your mother hears of this;" but I heard no more; I had fainted from loss of blood, and I did not recover my senses till I found myself in my own bed, with my mother's mild eyes, full of sorrow, looking down upon me.

Notwithstanding the great cause she had to feel anger at my conduct, which was in direct opposition to her wishes and even to her commands, so frequently expressed, I had little cause to fear a scolding while I was still confined to the house and suffering pain. And even when I recovered, her remarks upon the folly of my behaviour were made with such tenderness that, while I could not help admitting their truth, I felt that I loved my mother the better for her correction. I promised,—oh! how warmly I promised her, while the smart was still within my wound, and my face was yet swollen and inflamed, that I would never more be guilty of an act of disobedience; that I would, from that time, do only what I was sure must cause her pleasure, and that I would strive in all things to acquire a good name for gentleness and other female virtues.

Alas! a Kitten's resolutions, made in the midst of pain and sorrow caused through not attending to the advice of elders, are too apt to be forgotten, when the aches are gone and the grief has worn away; at least, to my shame be it spoken, it was so in my case, for when I recovered I was more than once guilty of acts of mischief, which, by good luck only, happened to be less serious in their results than the event of the rat-hunt.

A circumstance which helped to make me thus doubly naughty and disobedient, was the falling among bad companions. I had, at that time, the dangerous fault of easily making acquaintance, no matter whether the animals were such as I should or should not associate with. Not content also with simply speaking and being civil to them, I became at once extremely intimate, and therefore very naturally often found myself in places and among dangers which I had no right to enter into or incur.

There came into the town, from a distant and wild part of the country, a family of Cats, consisting of a father and nine daughters. They were strange, shabby, half-savage looking creatures, and, having lost their mother at an early age, had unhappily possessed no one who could restrain or teach them better, so had grown up more like Toms than quiet female Pussies. I was too young to know this at the time, and no warning voice had been raised against them; for, fearing I should be denied the pleasure of going out with my new acquaintance if I confessed to my mother that I knew them, I never said a word concerning them, but ran out to meet them on the sly. The elder Cats of the family rather frightened me, they were so terribly wild; but the three youngest, who were about my own age, I very much admired. They seemed so good-natured, so bold, and were so free in their manners, that we became, in a few days, the firmest friends; and although I was a little shocked at first at the naughty words they used,—the biggest, I am grieved to say, sometimes really swore,—yet I even got accustomed to that, and thought, silly Kitten that I was, that it sounded grand and spirited.

Many and many a time, when my good mother thought that I was visiting a relation or one of her own steady friends, was I scampering over the country with these dangerous playmates, until, had I not possessed so kind yet strict a guide at home, I should have become as bold and shameless as they. Fortunately for me, I discovered their real character before they had succeeded in ruining mine; and as the circumstance caused a final break between us, I will relate it just as it fell out.

At the distance of an easy walk from the city of Caneville was the residence of a very wealthy bloodhound, who was as proud of his noble descent as he was of his riches and influence. The grounds attached to his splendid mansion were very extensive and beautiful, and one portion, which contained some tall trees and low bushes, was called the "preserve," because birds of all kinds had their nests among the branches. In order to guard this property from thieves and intruders, several fierce dogs paraded about the grounds, and, as they had orders to kill all animals that were discovered lurking there, you may believe the place was tolerably quiet. All these particulars I only learned afterwards, when I had nearly fallen a victim to my folly; but I knew perfectly well that this ground was private property, and that I had no business whatsoever to go into it.

My three friends and myself, being out one day upon an excursion, such as I have described, I, having slipped away from home, as usual, on the sly, with only a little pinafore for clothing, came upon these beautiful grounds, and having crossed a park, where we rolled upon the green turf undisturbed, we at last stood in the "preserve."

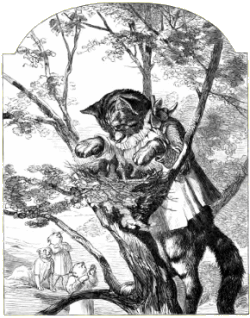

Here we were at once attracted by the quantities of birds which flew from branch to branch above our heads, and twittered gaily in the fancied security of their leafy homes. We looked, and sniffed, and watched them as they flew, until our mouths watered at the sight. Having eaten nothing since morning, our appetites were very keen, and the thought of a little poultry was not by any means a disagreeable one. But how was it to be procured? My friends, bold as they seemed, had a great objection to climb one of the trees to hunt for it; and I, although sufficiently strong and active to mount to the very highest in the course of a few seconds, had just sufficient sense of propriety left to feel that it would be wrong. What, however, will not the persuasions of the wicked sometimes do? Although I knew perfectly well that it was a great sin, that the birds were not mine, and that I had not only no right to them, but no right either to be within those grounds, I was, in a moment of weakness, prevailed on to climb a lofty oak, and seize upon the contents of a nest we could discover among the branches.

Quick as thought, I sprang upon the gnarled trunk, and mounted to the upper boughs; in a few seconds, I stood high up in the air, with one foot resting on a convenient ledge, my fore-paws outstretched upon a nest, wherein three half-fledged birds were chirping, one of which had opened its beak at my approach, as though I were its mother, whom it asked for food.

At another time I should have been touched at the spectacle of these little helpless creatures, and could have found it in my heart to place something in their yellow mouths; but now giving heed only to my voracious appetite and the cries of my friends, who kept calling out to me to pitch them down, I seized them cruelly by their necks, and cast them, one by one, below, desiring my companions, as I did so, not to divide them till I had descended to have my share.

Imagine, however, my astonishment, my anger, at their ingratitude, when, instead of waiting my coming, each seized a bird as it fell, and began devouring it with all speed, paying no more attention to my claims or words than if I had been a stranger, instead of their friend and the provider of the feast.

Enraged at their baseness, I had commenced my descent, to punish their perfidy, when the terrible sound of a dog's voice broke upon my ear. From my leafy hiding-place I peeped, in trembling, below, and saw two enormous brutes rush from a neighbouring bush, and, with a tremendous growl, fall upon my ungrateful companions. In an instant one was seized by the back of the neck, and dragged off, I knew not where; the other two fled, with shrieks of fear, pursued by the remaining dog, which, I suppose, had been attracted to the spot, with his companion, by the cries of the Cats, when telling me to throw them down the birds.

Oh! how my heart beat as I witnessed the scene I have just described, and thought that I too might have been one of the victims! Even now I might be unable to escape, but lose my life in attempting to get away. How bitterly I reproached myself for having been weak enough to choose such creatures for associates! What advantage had they ever procured me? Had I learnt from them one single thing of good? I grieved to think, not one. But what evil had their acquaintance not brought me? I had been not only guilty of disobedience to my mother,—that tender mother!—but I had trespassed upon the property of others: I had taken that to which I had no possible right; I had caused the death of three little creatures; and I had not even had the consolation of putting the smallest bit of one of the innocents into my own mouth. All these reflections passed through my Cat's brain, as I sat shivering on my elevated perch; and I resolved, as I had so often resolved before, that if I got safely out of this danger, nothing should induce me to commit such sins, or trust to such worthless friends again.

Whether my repentance had anything to do with my escaping from my difficulties with a whole skin, I cannot say; but it is certain that when, after darkness had settled on the earth and all around was silent, I ventured to descend from my hiding-place, I succeeded in making my way out of the "preserve," and park beyond, in safety, when I took to my heels with all speed; nor did I stop till I had reached my own quiet home, which I stealthily entered through an open window.